Folders |

All Eyes On Us - The Story of the 1998 Wyatt TX Record-Breaking RelayPublished by

All Eyes on Us The Untold Story of the Greatest Relay Season in Prep History A story by Dave Devine

“Mr. Speaker, I rise today to bring to your attention the remarkable efforts and acclamations of the track team from the Chaparrals of O.D. Wyatt High School in Fort Worth, Texas.” - Rep. Martin Frost, U.S. Congressional Record, June 18, 1998 “Man, there’s a lot can happen in a four-by-one.” - Michael Franklin, O.D. Wyatt _________________ The knock on the hotel room door comes earlier than expected. Much earlier. Sprawled on the beds, lanky and tangled among rumpled sheets and folded hotel pillows, four high school boys stir, none wanting to answer the door. Each of them recognizing the knock. They blink and look around. Trying to make sense of the room edges in the available light. Assembling pieces of the night before. Clinging to the vestiges of sleep they were able to claim before this interruption. The knock comes again, unrelenting. It’s Saturday morning, hours until the most important race of their young lives, but none of them are ready to wake up. That’s because they all ducked curfew last night, slipped from this room into the cool Texas evening and spent hours slinking through the hotel, visiting other teams, in and out of rooms. Kid stuff, they’ll say, years later. Running around, chasing girls the whole night. They were supposed to be under the watchful eye of a former athlete from their high school, an alum who became a federal agent and was brought in by their coach for the express purpose of keeping track of his young charges. Keeping them separated from an increasingly clamoring public. But these kids, they slipped the federal agent, too. The knock on the door? That’s Coach Lee Williams. In a moment, he’ll come in and rip into the teenagers. Give them a good chewing out for their nocturnal exploits. And then he’ll barely talk to them for the rest of the morning. Twenty years later, one of the boys now rousing from sleep —Mario Wesley — will vividly remember that contrast. The coach’s brief, stern reprimand, his prolonged silence. Coach didn’t have to tell us too much, he’ll recall. We already knew what time it was. It was 7 a.m. But that’s not the time Mario is talking about. Because today is the Texas State Track and Field Championships. May 16, 1998. And the time these four sleepy boys will author on the stadium track this afternoon is the only time anyone will remember. It will be talked about for decades. * * *

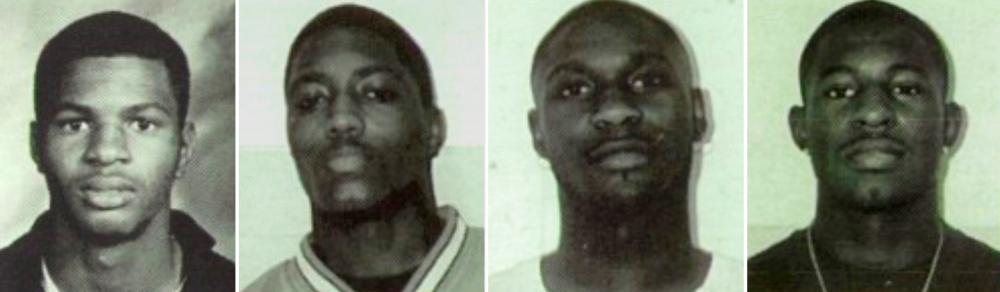

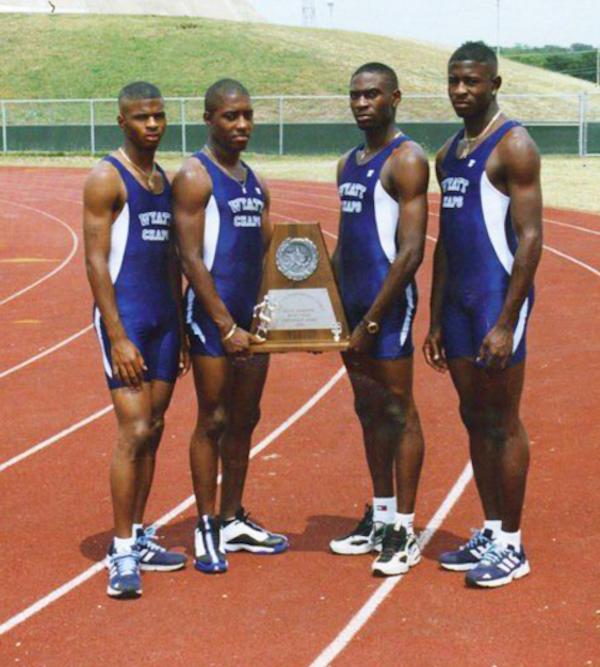

By the time the boys on the 4x100 relay from O.D. Wyatt in Fort Worth, Texas, arrived at the 1998 UIL 5A state meet, they were already stars. In the Region I qualifier at Texas Tech in Lubbock, they clocked a 39.99 winning effort, the first sub-40 electronic time in prep history and a new national record, toppling a 40.09 mark by Jasper, Texas, from 1991. The performance left track fans in the Lone Star State — and far beyond — completely abuzz. At a time when the Internet was not yet widely accessible, and national track and field websites like DyeStat were still in their infancy, news spread the old-fashioned way. Phone calls. Newspaper articles. Word of mouth. And in a state where sprint relays are marquee events, where football fast in the fall becomes track speed in the spring, the fact that one school found four boys to relay together in under 40 seconds was big news. It might have seemed like the Chaparrals exploded on the scene, but like most “sudden success,” their breakthrough was years in the making. Led by three seniors — Monte Clopton, Michael Franklin, and Demario “Mario” Wesley — and fronted by Mario’s precocious sophomore brother, Milton, the quarter had been poised for state meet success a year earlier, before torn ligaments in Michael’s ankle and bone spurs on Mario’s foot derailed their hopes at the regional meet. The collapse of their state title dreams in 1997 only left them hungrier the following spring. A mid-season race at the Carter Shootout showed Coach Williams this might be a special group. Even with an uncharacteristic breakdown on the second exchange, the coach watched as his star anchor, Mario, received the baton in third and proceeded to mow down the field. “They saw it, and I saw it too,” Williams recalls. “We had a chance to run under 40 seconds.” The coach, after tinkering with his line-up in the early spring, knew he’d found a winning combination. “Milton could run a good curve and Monte could run a good straightaway,” he says. “And then hand off to Mike, who could run the second curve, and then Mario—he could split almost 9-flat. I wasn’t gonna change anything.” The team grew in confidence and reputation, spawning the sort of adulation typically reserved for football or basketball stars on the Fort Worth streets where they grew up. “After a while,” Michael says, “we started calling ourselves The Four M’s: Milton, Monte, Mike and Mario.” The growing attention caused Williams to take extraordinary measures to insulate his team from the pressure. At meets, he insisted they warm-up in a separate area, removed from family, friends and other teams. He kept them from the track until immediately before races. And to manage that separation on the weekend of the state meet, he recruited a former Wyatt runner who’d competed at Rice University before a career with the Drug Enforcement Agency. “That’s true,” Williams says, “I had him watching the kids and keeping people away.” While the Chaparrals were almost certainly the only team at the state meet under the protection of a federal agent, the crowds and the escalating pressure weren’t the only concerns. At that time in Texas, lane assignments for the 4x100 final were generated a week in advance, via a blind draw. When the start list came out, Williams and his team were stunned. Wyatt, the fastest relay in high school history, was relegated to Lane 1. The layout at Darrell K Royal–Texas Memorial Stadium only amplified the concern. Wedged around a football field, the track had long straights and tight curves, with a metal rail edging the entirety of Lane 1. It was nothing like their oval back in Fort Worth. Similar to many Texas high schools at the time, Wyatt had a dirt track where runners scratched out dusty laps around a rutted field. Unlike like most, theirs was next to a federal correctional facility. During afternoon practices, the high school athletes would watch inmates exercising in the prison yard as they completed their own workouts. Some days, the team practiced at nearby Texas Christian University (TCU), but even that all-weather track lacked the metal rail they would encounter at the state meet. Coach Williams wasn’t about to let any of that serve as an excuse. “We didn’t have time to cry about what we didn’t have,” he says. Accustomed to traveling to TCU for workouts, Wyatt spent the days before the state meet commuting more than thirty minutes across town to the University of Texas Arlington, where they found a layout that closely matched the one in Austin — including the rail. “That whole week leading up to State,” Monte recalls, “we worked out in Lane 1, we did our handoffs in Lane 1, so that by the time the track meet came, we were ready.” The morning of the championship, as planned, they completed warm-ups and last-minute preparations at a practice field outside the stadium. “We believed in Coach Williams,” Milton says. “We knew he didn’t want all that attention around us, because we were already hyped. We liked the attention.” When the team finally climbed into a van that delivered them to the stadium, exited the van and entered a tunnel to the track, they received all the attention they could handle. And they suddenly appreciated why Williams had kept them separated. “I just remember walking on the track,” Monte says, “and it was like — all eyes on us. The whole stadium.” “Like a football game,” Milton says. Except this wasn’t the Texas Longhorns, 100-strong, charging from the tunnel into the embrace of a raucous home crowd. This was four boys from Fort Worth, strutting out like rock stars. “When they walked out there,” Coach Williams says, “and they acted like they were the only ones on the track, I knew they were ready to run.” The noise was deafening. “It was great,” Mario says, “but none of that noise mattered.” Soon, they knew, would come the reality of a state final. Stern officials and exacting clerks. A starting line and starting blocks and a single baton, placed in the hands of a sophomore. Soon, it would all be on…

MILTON “He was the young one out the bunch. We call him Little Milton.” - Michael Franklin

When Milton Wesley arrived at O.D. Wyatt as a freshman in the fall of 1996, he already had his sights set on making the school’s vaunted 4x100 relay squad. Not eventually. Not after working his way up, putting in time on junior varsity units and B-teams, the way his older brother Mario had done. Milton wanted the stick that year. As an eighth grader, he attended Mario’s track meets and watched his then-sophomore brother rip around the track with his teammates, wondering if he had what it took to break into the line-up as a ninth grader. “I was always asking him if I had a chance to make the relay,” Milton recalls. “I already had my eyes set on that.” If his goals were ambitious, they weren’t entirely misplaced. He and Mario had been competing together on summer club teams since they were six and seven years old; they’d had enough success in national Junior Olympic and AAU meets to suggest it wasn’t crazy for Milton to imagine joining his brother on the Wyatt crew. At the time, there were two prominent pairs of brothers in south Fort Worth track circles — the Braziels, Jerome and Jerrod, and the Wesleys. While the Braziels attended crosstown rival Dunbar for high school, and the Wesleys ended up at Wyatt, all four hooked up for relay success on the summer track circuit under the Hallmark Club banner. And Milton was always the one jumping up a classification to fill out the squad. Even at a young age, he was used to coming out of the blocks. “He’s been running like that ever since he was eight years old,” Mario says. “And he always ran first leg.” Somewhere along the way— due in part to his father being named Milton, but also to his size relative to the boys he ran with— he got tagged as Little Milton. The moniker followed him to high school. By the time spring track rolled around his freshman year, despite being the new kid, the little guy, Mario’s kid brother, one thing was abundantly clear: Milton was used to punching way above his weight class. “There was other dudes,” Mario says now, “juniors and seniors that should’ve been on that relay, but they wasn’t faster than Milton. He had the heart, he had the talent, and once Coach Williams saw him run a few times, that’s all he needed to see.” Williams also had a personal connection to the Wesley boys. “I competed against Mario and Lil’ Milton’s daddy when we was in high school,” he recalls. “And he told me, when they got to Wyatt, he said, ‘Lee, those’re your boys now.’ He knew I wouldn’t do anything to get them hurt. He trusted me, and I appreciate that.” The elder Milton trusted Williams; the coach trusted Little Milton. So did the rest of the squad. “He was a sophomore, running like a senior,” Mario says. “Every weekend.” But if Milton carried the confidence of his coach and teammates to the starting line, it didn’t erase the pressure of being an underclassman trying to deliver a state title to a group of last-chance seniors. “At times it was very difficult, being a sophomore and leading off,” he acknowledges. “But I believed I had a good start. I always believed in my takeoff.” Whenever doubts arose, Milton settled into the surety of that start. His familiar explosion out of the blocks. The way he got out hard, handled his business, attacked the stagger. Which is why the state meet had him worried. “We were all nervous about being in Lane 1,” Milton remembers. “Because when they shoot that gun, it’s a looong way back to us.” * * * The sophomore settles into the blocks. Rolls the baton between his fingers. Glances at the way the track alleys and curves away from him, seemingly forever. Buried in the stagger, just like he knew they’d be. Fastest team in history, stuck on the inside. It feels like a slight, a diss. The metal rail to his left, too, inches from his ankles. So unfamiliar, hemming him in. He tries to block all that out. The nerves mean he’s ready. He feels the weight of the eyes staring down on him from the stands. The expectations that come with being the first high school 4x100 team in history to go under 40 seconds. Friends, family, teachers, coaches. Rivals that want to see them fail. Old trackheads up in the bleachers. Cat calls and shouts of encouragement. He tries to silence those voices, too. There’s only one voice that matters now, and that voice is speaking: Runners to your mark. Between that command and the word “Set,” Milton clears his mind. Empty. When the gun goes off, he’s out fast, like usual. He leans into the curve, wary of the rail. He gets after the stagger, handles his business, zeroes in on his man. The dude waiting for the stick…

MONTE “He’s the one who kept us going. The one who always had something to say.” - Mario Wesley

Every squad needs a talker. A motivator. A hype man. For the Wyatt track team in the late ‘90’s, that guy was Monte Clopton. “If somebody would talk noise at us,” Michael recalls, “Monte would be the one that’d talk noise back.” Monte, even now, doesn’t shy away from that characterization. “I was — I guess you could say — the wild one,” he acknowledges. “If there’s gonna be a battle, as far as running, or a fist battle, I’m going to be the first to jump.” Unlike the other three boys on the record-setting quartet, Monte hadn’t risen up through the summer track circuit. He arrived at Wyatt as a freshman transfer from Southwest High, a confident gridiron speedster buoyed by success between the yard lines. And he made sure to put his new track teammates on notice. “I really thought I could run,” Monte says. “I talked a lot of noise. Real arrogant.” Coach Williams knew exactly what to do with his assertive new arrival. He placed Monte in the anchor slot of the 4x100 at the first junior varsity meet of the season. “I was talking noise to everybody,” Monte remembers. “Over there like, I can’t wait to get the stick. But Coach Williams— he knew how to get your attention.” Monte received the baton with a narrow lead, his big chance to show off his wheels. Two rival teams blew past like he was standing still. When he finally caught his wind and glanced sheepishly at the stands, he found his coach chuckling. “He goes, ‘Hey man, looks like you got stuck in quicksand.’” Monte was furious, but the coach put the whole thing on repeat the next meet. Again, on anchor. Again, the mouthy frosh was run down in the homestretch. Disheartened, Monte started ditching practice. Eventually, Williams made a visit to the Clopton household to find out where his JV anchorman had gone. “I’m an old school coach,” he says now. “You have to go by and talk to the parents sometimes. You gotta know what’s on the kid’s mind. They might have something on their mind that don’t have anything to do with athletics, and you got to get all that straightened out. If you don’t, you could wind up losing a kid.” He doesn’t mean from the team. Or the school. Williams coached long enough to lose several young men to the violence that swirled in south Fort Worth in those days. It shattered the coach every time. His wife, too. She often traveled to meets, became close with the boys, treated them like family. And more than anything else, that’s what Williams tried to cultivate— a sense of family on the Wyatt squad. A place of discipline and love. Tough love, sometimes. Which meant the occasional house call. Seated in the Clopton’s living room, Williams explained that he’d put Monte on anchor to get his attention, teach him his place, but assured the precocious frosh he was brimming with potential. Monte was convinced to rejoin the team. He pulled himself off the relay and focused on improving his speed. He bought into Coach Williams’ system, absorbed the tough love, embraced the exhausting workouts on humid, airless Texas afternoons. That summer he joined a club team, a rival to Hallmark, and returned sophomore year ready to climb the ladder back onto the Wyatt relays. But if Monte was finding a home on the Wyatt track team, it wasn’t enough, in those early days, to keep him from the occasional pull of easy money on the neighborhood streets. The drug dealers in south Fort Worth knew about the Wyatt relays, too. One day Monte was working a corner, hoping to turn some quick cash, when a dealer named Uno confronted him. “He was like, ‘Man, what you doing out here?’” Monte explained that the latest Air Jordans had just come out, and he couldn’t afford them. Disgusted, Uno asked the price of the sneakers. Monte told him: $125. “He gave me two-hundred bucks and said, ‘Man, don’t let me catch you out here no more. This is not for you.’” Monte stayed off the corners after that, devoted even more energy to football and track. In the fall of senior year, as the gridiron season drew to a close, Monte — ever the hype man — told his principal that Wyatt would break the national 4x100 record in the spring. “He looked at me crazy, like I was out of my mind.” But Monte knew how impressive the team had looked junior year, before injuries set in. He was well aware of the pieces coming back. “I knew, once we linked back up, it would be real dangerous.” * * * When the gun goes off, Monte is in the middle of a prayer. The muttered words slip away, forgotten, as he snaps his focus to Milton, now barreling toward him. Ten seconds and closing. Fast. When the sophomore arrives, Monte’s ready. He snatches the baton into his left hand, tucks it there, beelines down the backstretch. Only it doesn’t feel like a track anymore, or even a stadium. It feels like a tunnel. His vision narrows to a slender aperture, a sort of telescoping sensation. The roaring crowd fades away. The sprinters to his right, the rest of the field, it all sinks into the scenery. Monte feels like he’s floating. Feet not even grazing the ground. A drummer, he slips into a 10-second tempo. Allows his churning arms to bring the meter and the groove. The staccato beat. Feels the way that lifts and propels him. All rhythm. He makes up the stagger without trying, focused only on the space inside his lane. The things he can control. A hand flares back, an open palm. He gets the stick off, left to right, low but clean. Rote, like something memorized. A piece of music. Monte to…

MICHAEL “Michael was kind of quiet, he didn’t say too much. He was just ready to run.” - Mario Wesley

Michael still remembers the feeling. The slow rise, as soon as they got the word from Coach — maybe in the morning, maybe after lunch — that tasted like a mix of dread and resignation. Once a week, Coach Williams would announce that the workout for the day was the 45-Second Run. Nothing fancy — just all-out on the track for 45 seconds. One at a time, running solo, get as far as you can. “He’d tell us that in the hallway,” Michael remembers, “and it was like, ‘Aw, maaan.’ Rest of the day, we’d all start focusing on how we were going to run it. We’d be warming up like it was a track meet, just to run 45 seconds.” In some ways, it was more intense than a track meet. The lingering memory and sting of those efforts—for all four men, now in their late 30’s — is an indication of just how cutthroat the Wyatt sprint workouts became as the team rose in stature and talent. “We were always so competitive,” Michael says. “In that workout, we each tried to cross the finish line. Make it a full 400…in 45 seconds.” He lets out a low Pshhhh, still in disbelief.

Michael started as a short sprinter when he was a freshman, but Williams, always on the hunt for quarter milers, asked him to step up to the 400 so Mario could focus on the 100 and 200. He had occasional company in the form of Milton and Monte, reluctant one-lappers pressed mostly into 4x400 relay service. “Those guys definitely didn’t want to run the 400,” Michael says, laughing. Michael, however, embraced the distance. He appreciated the strength it gave him, the familiarity with angling into the curves that would assist with shorter relays. Eventually, he’d run 47.86 to finish third in the 400 at the same state meet where Wyatt cemented their relay legacy. But his status as a 400-man had another advantage. It placed those 45-second sprints squarely within his wheelhouse. And made them a major point of pride. “Those days, man, I loved them.” Mostly, he wanted to beat Mario, just to upset the speed charts and nail down some bragging rights. But Mario never went quietly on those days the team tried to solo the oval in 45 seconds. “When you’re that fast,” Michael acknowledges, “you can move up to the 400, just like Usain Bolt. You may not like it, but you can move up.” Mario and Michael had more in common than a heated workout rivalry. Both were on the reticent side, both preferred to let their feet do the talking. Even now, that’s how Michael is described. “They’d always say to me, ‘You’re the quiet one, you keeping to yourself.’ Well…I’m trying to focus. I played the race out, over and over in my head, before I went out there and performed it.” Even before high school, Michael and Mario hooked up on relays when they ran for the same summer club. Always in the order they occupied at Wyatt: Mike on the curve, Mario on anchor. “Since we were thirteen, it just came natural with us,” Mario says. “Him running third, me running fourth.” That potent connection, that flow between friends, only grew as they charged deeper into their senior season. “We were on a mission to make it back to State,” Michael says. “Senior year, same relay, we were like, ‘It’s time to finally win this thing.’” * * * Michael takes off and the stagger evaporates. The first lane, which felt like such a hindrance 20 seconds earlier, becomes a benefit. A boon. Michael is even almost immediately. He sweeps past on the inside, draws a bead on Mario around the tight turn. Makes the meters vanish. There won’t be a verbal command or a call for the stick. It’s too loud to hear it anyway. At this point, baton exchanges with Mario are like tying a pair of shoes. Used to have to pay attention, think it through, but not anymore. He could do it with his eyes closed. In a dark room. That’s how it feels. Automatic. Mario takes off like he was shot out of a cannon, but Michael doesn’t panic. He knows the hand is coming. He senses the approach, measures the real estate. Feels it like a shoelace. They use every inch of the exchange zone, both their arms fully extended. Risky, but perfect. For once, Michael isn’t the quiet one. He trails Mario into the stretch, pumping his fist and hollering— Go! Go! Go!

MARIO “I knew once Mario got it, wasn’t nobody going to catch him.” - Monte Clopton

Coach Williams goes quiet for a moment. Lost in thought. “I’m trying to remember the meet…” Sometimes, a coach sees something before anyone else. An insight, honed through years of practice, that provides a hint about the future. A glimpse that might change the trajectory of a season. Or a career. Like the moment you realize that the young man who’s been running in front of you for weeks might be fastest kid you’ll ever coach. “It was against Dunbar,” Williams says, details flooding back. A fierce rivalry, because athletes at both schools ran summer track together. School pride and club reputations on the line. “They had a little mouthing going on,” Williams says, chuckling. “I guess they ticked Mario off, and that’s when he showed — we call it ‘gear shift talking’ amongst the coaches— but he showed another level that he had. And when he put it down, he put it down.” Mario, still raw as a sprinter when he arrived at Wyatt, displayed—for the first time his coach could recall— the sort of speed that can’t be taught. “I got so excited,” Williams remembers, “my hands started shaking just looking at the stop watch. That’s when I knew — this boy can run.” As he says this, it’s clear that the old coach has two versions — two distinct pronunciations — of the word “run.” There is the simple, prosaic verb: I watched them run. And there’s the way he articulates the word when he’s implying something deeper. Something ephemeral and rare and difficult to wrap your head around. Boy could run. “At sixty meters, he just had another gear,” Williams says, wrestling to describe a phenomenon that experience and science tells him is counterintuitive. “I know — Look, I know you’re decelerating during that phase, but…he had another gear.” It took some time for that talent to emerge. Mario didn’t make varsity his freshman year. The kid who would go on to earn nicknames like Flash and Smoke arrived at Wyatt as another swift kid from south Fort Worth trying to dodge the influences of drug dealers and gang bangers. “It was tough,” Mario says now, “there was gangs everywhere. You had to stay focused, not get involved with all that. A lot of people that was fast — you know, football fast — they all got into the gangs.” Coach Williams, recognizing that Mario’s burgeoning talent didn’t quite match his maturity, elected to bring him along slowly. “He was still trying to grow up a little bit,” Williams recalls. “Plus, he didn’t know what he could do. I kind of let him just come along and grow up, not put that pressure on him.” A key change between freshman and sophomore year helped Mario improve his focus, both in the classroom and on the athletic field. He moved out of his parents’ house and into the home of his aunt, Bernice Wesley. Still close with his parents, he knew that living with his aunt would help him “get away from all the noise going on in the neighborhood.” By the end of his sophomore year he was fourth in the 100 at the Texas state meet (10.48) and, before an untimely disqualification, third in the 200. The 4x100 team that year also finished third, in 40.78. Junior year began promisingly enough, but ended with the frustration of bone spurs at the regional. By senior year, everything was riding on a final push to the state meet. National records were nice, but for Mario, they were secondary. The fastest runner on the fastest relay squad ever was focused on one thing: Delivering his crew to the top of the UIL podium. * * * Warming up was all business. Windbreaker hoodie up, cinched tight, laser focus. Strides and quick handoffs. Thinking through the phases, the acceleration, the execution. The path to redemption. Monte to Michael showed how much damage had been done. The stagger was all but gone. And now here comes Mike, rolling like a freight train. It was always coming to this moment. This exchange. The celebrated sub-40 is pointless if Mario gets run down in the final straight. So, he makes sure that doesn’t happen. He feels the baton into his fingers from Michael’s outstretched hand, then covers the homestretch like a piece of prestidigitation. A disappearing act, no curtains. There, and then… Gone. Nobody within a Texas mile. A dip at the line, a deceleration into the curve, an almost unthinkable time frozen on the stopwatches. And when Mario turns to jog back to the finish, the second-place team is celebrating because they thought they won. Lost track of the anchor from Wyatt. 9.04 on the split. 39something on the clock. Doesn’t matter. The state title’s the thing, and they locked it up. Michael mobs him, and then the others are there, Monte and Milton, fresh off a half-lap celebratory jog where they witnessed stunned fans displaying watches to each other, shaking heads in disbelief. In the midst of a group hug, Monte tells them all to look at the scoreboard. Official time is up. 39.76 The announcer attempts to inform the crowd that it’s a new national record, but even that gets lost in the roar. Then a security guard is hustling them from the infield. Coach Williams’ federal agent buddy meets them in the tunnel. It’s mayhem. They can barely make it through for the crush of the crowd. * * *

The weeks after the state meet unfolded like a victory tour for the Chaparrals. First came the Golden South Classic, in Orlando, Florida. There, the foursome sought to answer swirling doubts about the legitimacy of their sub-40. “I mean, we got invited,” Mario says, “so we went. But there was some teams saying we didn’t run no 39, that it was fake. That’s another reason we wanted to go— to show them.” Wyatt answered the doubters by dropping a 39.82 against Florida’s best squad, Boyd Anderson. Anderson’s runner-up mark — 40.09 — remains the best time in Florida prep history and the fastest non-Texas clocking in the books. For good measure, the Wyatt quartet agreed to meet Anderson in the 4x200, an event they had rarely run, since the relay wasn’t part of the Texas state meet format for boys at the time. Wyatt proceeded to run 1:23.31, blowing away the 1:24.79 national record that Long Beach Poly of California had set earlier in the season. Michael, who anchored that 4x200, recalls they essentially ran it on a whim. “Those guys wanted to run against us, and we were like, Okay,” he says, still sounding bemused. “You had three of the four guys who were on the mile relay, we already had the speed, and you want to run us in a four-by-two? Okay, that’s fine.” They defeated Boyd Anderson by nearly three seconds. Twenty days later, the squad was in Raleigh, North Carolina, for the Foot Locker National Scholastic Outdoor Championships, a precursor to the current New Balance Nationals Outdoor. Lured, in part, by the promise of racing the storied program from Long Beach Poly, the team was disappointed when Poly failed to materialize. They still put on a show. Wyatt won the 4x100 in 39.92 (after a 39.80 prelim), again over Boyd Anderson, then stole a special section of the 4x200 in 1:23.67, demolishing the field by almost three seconds. At the conclusion of the North Carolina meet, Wyatt owned the five fastest 4x100 times ever recorded, all under 40 seconds, and the two best 4x200 marks in history, in an event they contested as an afterthought. “Once we ran 39,” Milton says, “hate to say, but it was easy. We could just keep doing it.” After the dazzling six-week odyssey, life took the four Wyatt runners in a variety of directions, but they all eventually ended up back in the Fort Worth area. Milton had two more successful years at Wyatt, then attended community college in Houston for a time before returning north. For the last 11 years he’s worked at a printing press in Grand Prairie, 20 miles east of Fort Worth. He has a daughter now, but some still call him Little Milton. “It still floats around,” he says, laughing. “If somebody calls me that, I know it’s somebody close to me, that really knows me.” Monte competed in track at Cal State Riverside, where he received an associate’s degree. His plans to transfer to a Division 1 track program at a four-year college were derailed when he accepted money from a Riverside alum and lost his NCAA eligibility. Now a father of three, he works for a Fort Worth waste management company. His real love, however, remains track and field. He and Mario coach for the Hallmark Club, the same youth team that several of the Wyatt sprinters competed on years ago. “It’s everything for me,” he says. “I do it because I love kids and I love the sport.” Michael, who ran for two years at Texas Tech before becoming an All-American at the University of Texas, is now a train conductor. His typical route includes runs out to Amarillo or Oklahoma City, but lately he’s been pulling night shifts in the railyard so he can watch his children compete in sports. His son, Michael, played quarterback for Wyatt last season and is running track for the Chaparrals this spring. Mario attended Garden City Community College in Kansas, then transferred on scholarship to TCU. After a truncated career riddled with hip and hamstring injuries, he left TCU to pursue track opportunities overseas. The injury cycle continued, however, and eventually Mario decided to hang up his spikes. “I just gave up,” he says, “realized I had to face reality and get a job.” Today, he works in street operations for the City of Fort Worth, helps to raise three children, and coaches Hallmark track in the summers. Two of his own children compete for the club, including his son, Mario. Coach Williams retired last spring, after a storied 41-year career at Wyatt. When he’s pressed about plans for his newly-flexible schedule, he laughs at the predictability of his answer. “Well, this afternoon I’m heading out to watch a track meet.” Which seems to be the common thread. Twenty years after the most remarkable relay season in prep history, Michael has a son named Michael. Mario has a little boy named Mario. Both run track. Michael works the night shift so he can attend Wyatt meets. Monte and Mario coach for the Hallmark club, imparting many of the aphorisms Coach Williams instilled so many years ago. Milton helps out when he’s in town, hopes to get his 2-year-old daughter into the sport when she’s older.

Track, still the thread that runs through it all. Only two other high school teams, both from Texas, have dipped below 40 seconds in the years since Wyatt dropped five sub-40’s that magical spring of 1998. Forest Brook of Houston ran 39.95 in 2001, and last season Port Arthur Memorial gave the record its closest shave—a stunning 39.80 at the Texas 5A state meet. Memorial also ripped a 1:23.52 for the second fastest 4x200 of all time. Mario and Monte were in the stadium watching it unfold. “I’m not gonna lie,” Monte says, “when the 4x100 crossed the finish line, both our hearts just dropped.” Only when the official mark hit the scoreboard could the two old friends breathe a sigh of relief. “We were like, ‘Wow, we dodged the bullet again.’” All four men are realistic, they know the records will tumble at some point. They’re aware of several Texas squads that represent a threat this spring. They’re familiar with the Anthony Schwartz-anchored American Heritage team in Florida, already dropping marks in the low 40-second range. History and stale sports adages assure them: Records are meant to be broken. But there are days, twenty years on, when they can’t help but wonder. There are days — perfect spring afternoons — when Mario and Monte stare out at a sun-warmed track crowded with children, when the laughter rises and the light falls a certain way, that the present feels like it’s blurring into the past. Time collapses, playing tricks with the years. “To this day,” Monte says, “when I walk on the track, I still feel like — at 37 years old — I still feel like I’m the fastest guy on the track.” He laughs, knowing how ridiculous that sounds. “I couldn’t even give you a good 50 meters, but when I step on the track, I feel like I got my bounce back.” At meets, sometimes, he watches the older kids. Their slick uniforms, sharp turnover, snapping exchanges. The way confidence and speed seem to drift off them like heat fumes. He shakes his head, then, remembering that feeling. Thinking about the similarities. The differences. “Sometimes I wonder — Man, how did we look in person?”

History for O D Wyatt H S Track & Field and Cross Country - Fort Worth, Texas

Show 2 more

|

Twenty years later — all that life, all those changes, and the records remain.

Twenty years later — all that life, all those changes, and the records remain.